Before we had our own heroes—before the Transformers transformed, before He-Man flexed, before the Ninja Turtles emerged from the ooze—we were raised by older gods. Mischievous, violent, wiseass icons who didn’t belong to us, but took us in anyway.

Bugs Bunny. Popeye. Tom and Jerry. Woody freakin’ Woodpecker.

They came from another time. Born in the black-and-white blur of Depression-era cinemas and World War newsreels. Survivors of studio politics, propaganda reels, and early syndication deals. And by the time Gen X found them—on busted TVs in overcrowded living rooms, Saturday mornings and after-school marathons—they’d already lived lifetimes.

But they didn’t feel old to us. They felt eternal.

These weren’t tidy, lesson-laden cartoons. They were weird, dangerous, unpredictable. Their universes didn’t make sense—and that was the point. They didn’t teach us to say sorry. They taught us to laugh in the face of chaos. To outwit a bigger opponent. To blow up the system and strut away without looking back.

And now? They’re gone.

Not in name—those names still float around, pinned to content that has all the flavor of soggy cereal. But the characters, the gods—they were taken from us. Sanitized. Hollowed out. Treated like old brands to be “updated” instead of mythic forces to be honored.

This isn’t just nostalgia. This is a cultural crime scene.

The Trickster, the Brawler, the Duo, and the Screech

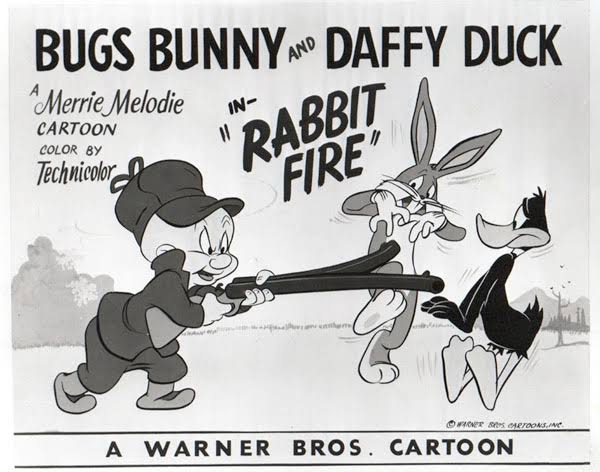

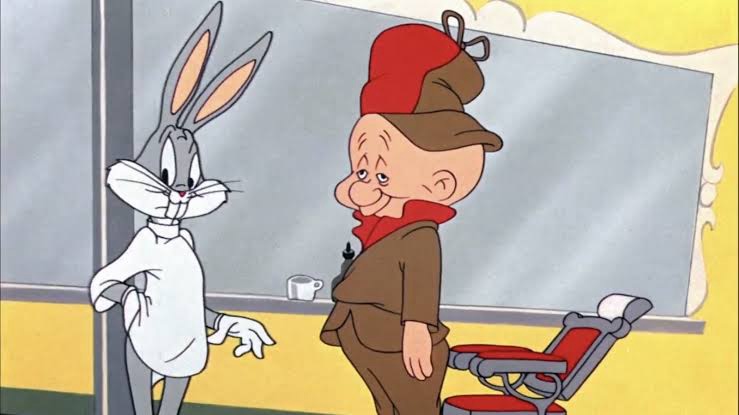

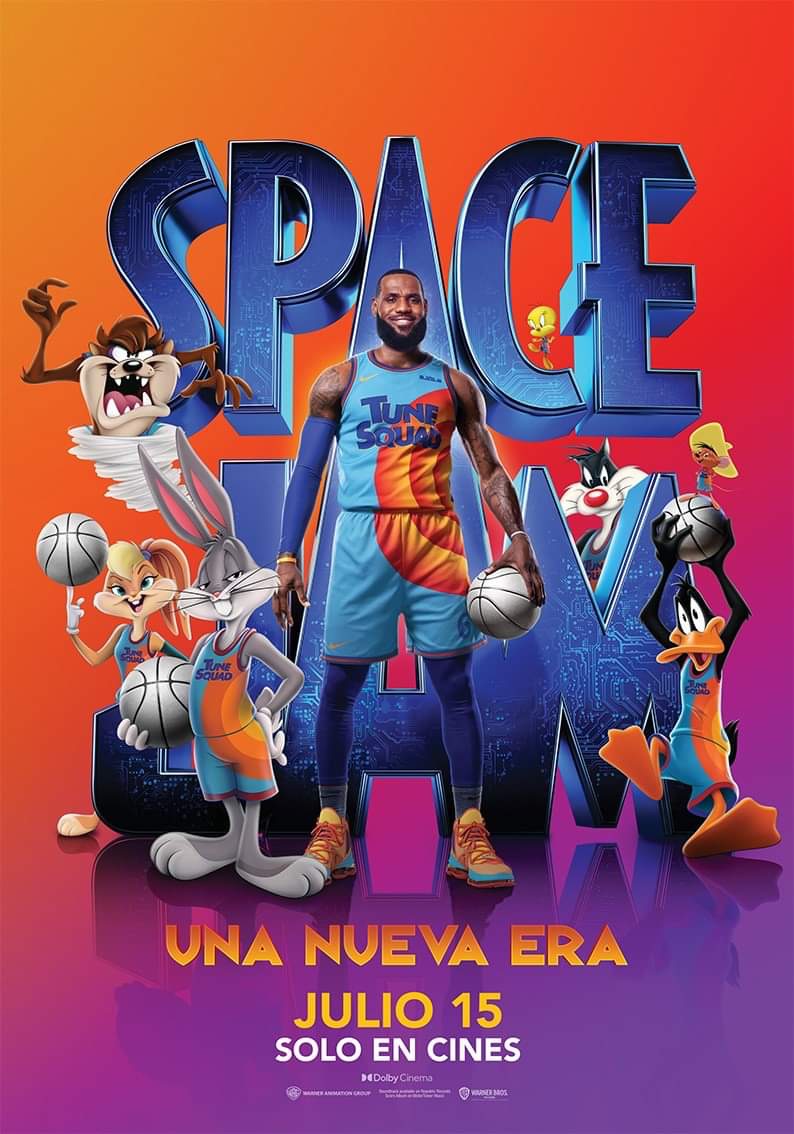

Bugs Bunny: The Bastard God of Cleverness

There was a time when Bugs Bunny ruled. Not in a boardroom. Not on merchandise. On screen.

He didn’t run. He didn’t flinch. He stood in the middle of the road with a carrot in his mouth and stared down authority—whether it was Elmer Fudd, a Nazi, or a Martian. He wore dresses. Quoted Shakespeare. Mocked his own animators. He wasn’t just funny—he was dangerous. A trickster in the old mythological sense. Loki with Brooklyn swagger.

You ever see What’s Opera, Doc? That’s the one where Bugs throws on a wig, a Viking bra, and sings Wagner while tormenting Elmer Fudd in full opera. It’s not just parody—it’s cultural subversion delivered with a wink and a drag queen flourish.

Gone is the Bugs who could outclass opera tenors while cross-dressing to confuse monsters. What remains is a memory, used mostly to sell streaming services that bury his real legacy.

Popeye: The Blue-Collar Warrior

Popeye didn’t fly or shoot lasers. He mumbled. He squinted. He ate canned spinach and punched his way to moral clarity. He was a Depression-era folk hero in sailor’s clothes—messy, righteous, and unbeatable.

He protected the weak. Threw down with bullies. Ended fights with a punchline and a boot. He wasn’t just a cartoon—he was a blueprint for a very specific kind of resilience. The kind born in a country broke, broken, and still standing.

He didn’t represent perfection. He represented persistence—in a world where bad guys always came back and spinach always worked.

We would never accept him today. A sailor solving problems with violence, muttering threats through a pipe, and navigating a love triangle with jealousy and haymakers? Doesn’t exactly fit modern IP guidelines.

So Popeye was put on a shelf. Rebooted occasionally with no punch, no grit. What’s left isn’t Popeye. It’s spinach-flavored safety.

Tom & Jerry: The Ballet of Pain

They didn’t need words. Just rhythm. Choreography. Symphony. Every chase, every trap, every frying pan was timed like a concerto.

There’s an episode—The Cat Concerto—where Tom plays Liszt’s “Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2” on a grand piano while Jerry torments him from inside the instrument. It won an Oscar. It deserved it. It was a duel in musical form—visual slapstick timed to virtuosity.

But then came the off-model years—the Gene Deitch era, where Eastern European outsourcing turned them into stiff, surreal caricatures. And after that? Endless reboots, half-baked movie tie-ins, “kiddified” versions that turned artistry into noise.

Gone is the Tom who played Liszt to bait Jerry. Gone is Jerry, the tiny avatar of chaos with perfect timing.

What’s left is noise. Brand. Loopable content. No soul.

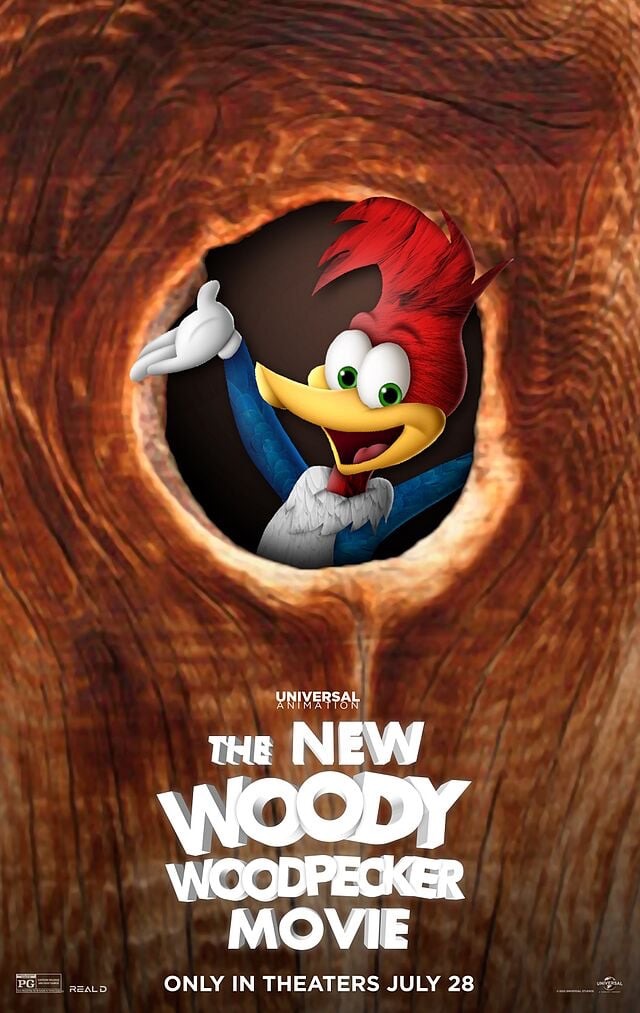

Woody Woodpecker: The Manic Phantom

Woody laughed in the face of logic. He was Bugs without the brakes. Daffy without the sadness. Pure chaos in bird form.

Where Bugs was clever and Daffy was tragic, Woody was loud. He didn’t play chess with his enemies—he just slammed the board into their face. And he loved it. He wasn’t trying to win. He was trying to make everyone else lose harder.

Take The Barber of Seville short—Woody gives a customer a shave so violent, so over-the-top, it becomes a kind of cartoon sadism. And it’s hilarious. He wasn’t a role model. He was a meltdown in feathers—and we loved him for it.

Gone is the Woody who faced death with a grin and a manic cackle. Now he’s a sterile CG character with a personality as sharp as a soup spoon.

And now?

Bugs is a mascot with neutered catchphrases.

Popeye is nostalgia merch.

Tom and Jerry are loopable toddler noise.

Woody is a CG husk with smoothed-over madness.

Their fall wasn’t just about time. It was about us.

What We Did to Them (The Long Fall)

Let’s not pretend we were innocent bystanders. We were the audience, the market, the consumers. We didn’t just watch the gods fall—we helped push.

It started with a budget crisis and ended with a factory line.

The Hanna-Barbera Shortcut

By the 1970s, Hanna-Barbera had found a new way to do animation: cheaper, faster, flatter. They stripped it down to bare essentials—stock backgrounds, limited motion, recycled sound effects. Every show became a remix of the last. Scooby-Doo ran past the same hallway twenty times. Dialogue replaced action. Movement got expensive. Standing still got normalized.

To their credit, Hanna-Barbera saved TV animation. But they also taught studios that kids would accept less. And once they knew that, they stopped aiming higher.

Clone Wars: Scooby-Doo and the Cut-and-Paste Apocalypse

When Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! hit in 1969, it worked like gangbusters. Teens. Van. Talking dog. Monster that turns out to be a dude in a mask. It was simple, cheap to animate, and endlessly repeatable.

And so, of course, they repeated it. Again. And again. And again.

By the mid-‘70s, the market was flooded with what felt like parallel universes of the same damn show. You had Jabberjaw, the talking shark who sounded like Curly from The Three Stooges. Speed Buggy, who was basically Scooby-Doo if he were a stoned dune buggy. Captain Caveman came out of a shag rug with a club and a scream. And then there was Goober and the Ghost Chasers, Clue Club, The Funky Phantom, and The New Shmoo—a fever dream of teen sleuths and awkward mascots with zero charisma but plenty of sound effects.

These weren’t characters. They were variables. Swap out the pet. Change the setting. Rinse. Repeat.

The networks didn’t care. The kids didn’t notice. And the gods—the real ones—Bugs, Popeye, Woody—were still hanging around in syndication, watching from the sidelines as their artform got copy-pasted into oblivion.

The Celebrity Cartoon Era: Fame Before Framing

The next trend was even stranger. Cartoons stopped being about stories or characters at all—they became celebrity delivery systems. Some exec somewhere had the realization: “Why invent a new character when we can just animate someone from TV?”

So you got The Fonz in space. Literally. They took Fonzie, gave him a time machine, and sent him into sci-fi hijinks with a talking dog named Mr. Cool.

Mr. T? He wasn’t fighting Clubber Lang—he was coaching a gymnastics team and solving crimes on weekends. Chuck Norris got his own squad of animated commandos. MC Hammer’s shoes were magical and fought crime. Gary Coleman became a guardian angel for confused kids. And Pac-Man was suddenly a suburban dad with a wife, two kids, and a ghost problem.

These shows weren’t greenlit because they were good ideas—they were greenlit because someone thought kids might recognize the name. They were brand extensions in search of an audience.

The old gods couldn’t compete with that kind of marketing logic. You can’t slap Popeye on a lunchbox next to Pac-Baby and expect it to move units.

The Toy Takeover: When Cartoons Stopped Pretending

And then came the big shift—the moment when cartoons didn’t even bother pretending to be anything other than commercials. Thanks to the Reagan administration’s deregulation of children’s television in 1984, the line between show and ad evaporated.

Suddenly, the screen was filled with characters who existed only to sell toys.

You had He-Man, yelling the name of his product line before every fight. G.I. Joe, delivering morals at the end of every episode, as if that excused the half-hour of laser battles you just watched. Transformers showed up from Cybertron with voices, alliances, and backstories that just so happened to match the figures on the shelves.

Then came MASK, SilverHawks, Thundercats, Visionaries, Bravestarr, and a dozen others—each one created not from a writer’s room, but from a toy design meeting. Vehicles transformed, figures glowed, accessories launched. And if they didn’t, they didn’t get a show.

Even the good ones—even the ones we loved—were built to sell, not to last.

And where did that leave Bugs? Or Popeye? Or Tom and Jerry?

They weren’t built for toy aisles. They weren’t collectible. They were performers, not product lines. They couldn’t compete with transforming tanks and holographic chest plates.

So they got pushed out of the spotlight. Their brilliance couldn’t be monetized as efficiently. So they were shelved.

The Babyfication of Everything

And just when it seemed like things couldn’t get weirder, the industry looked at its most chaotic characters—the anarchists, the iconoclasts—and decided: “You know what kids want? Baby versions of these guys.”

And so it began.

Muppet Babies opened the door. And through it came The Flintstone Kids, Tom and Jerry Kids, A Pup Named Scooby-Doo, and eventually Baby Looney Tunes.

Characters who once screamed, fought, schemed, and smashed were now singing songs about friendship and cooperation. Bugs Bunny, once the cool, cross-dressing, opera-trolling trickster god, was suddenly just another soft-spoken toddler learning how to share.

They didn’t evolve—they regressed. Bugs couldn’t cross-dress or quote Shakespeare. Tom and Jerry couldn’t smash each other’s skulls. Popeye couldn’t punch anyone.

It wasn’t reinvention. It was infantilization. Cultural sedation in pastel tones. The gods were put in diapers. And we were told to clap.

Trigger Warnings and Rubber Bullets: Who Killed the Edge?

For all the rubber-stamped clones, celebrity fever dreams, and weaponized toy lines—there was still something deeper gnawing at the roots of the cartoon gods. Something bigger than budget cuts or licensing deals.

It was fear.

Somewhere between Elmer Fudd’s shotgun and Mr. T’s gymnastics team, the world got nervous. Really nervous. About violence. About satire. About how kids might interpret jokes, or gender play, or irony, or a dynamite gag that ended with a puff of smoke and a blinking eyeball.

So the edge started to dull.

First it was small. They stopped airing the episodes where Bugs mocked Nazis. Popeye’s fistfights became handshake moments. Elmer lost his gun. The dynamite became silly props. Wile E. Coyote still exploded, sure—but with less fire. Less joy. More… apology.

Then Columbine happened. Then 9/11. Then the age of comment sections and constant outrage and corporate risk aversion.

And suddenly, the idea of a cartoon that challenged anything—anything—felt radioactive.

It wasn’t just about guns or gags. It was about the death of the trickster. The jester. The weirdo. The anarchist who could get under your skin and make you laugh at the system.

We softened. And the edge dulled.

But the edge isn’t brand-safe. It’s not testable. It’s not good for quarterly forecasts. So studios slowly sanded it away. Not because audiences demanded it—but because someone, somewhere, might complain. So they played it safe.

And we? We watched it happen. We didn’t light the fire, but we stood around warming our hands while the old gods melted down.

We didn’t ask for Bugs to be neutered. But we let him fade.

We didn’t demand Popeye back. We just shrugged when he disappeared.

We didn’t riot when Woody was replaced with a lifeless 3D shell. We just changed the channel.

The kids who came after us didn’t know what was missing. Their humor became either soft and wholesome, or ironic and detached. Bugs was neither. He was engaged. He cared. He was mad, and brilliant, and in on the joke.

And he’s gone.

So who killed the edge?

Boomers made it.

Gen X watched it.

Millennials filtered it.

Zoomers grew up without it.

Nobody flipped the switch. But all of us stopped paying the electric bill.

Let the Gods Return

We didn’t just lose cartoons. We lost archetypes.

We lost the loud, weird, violent, joyful chaos that told us it was okay to be strange. That cleverness beats power. That laughter can be a weapon. That you don’t have to be perfect to be great.

Let Bugs be smug again.

Let Popeye punch again.

Let Tom and Jerry smash each other into musical bliss.

Let Woody scream.

They weren’t meant to be babysitters.

They were meant to be remembered.

They raised us too. And we still owe them something.

These weren’t just cartoons.

They were gods.

And some of them still walk with us.

If you want to see the pantheon in more detail, the next doors are open:

Meet Bugs Bunny: The Trickster God of Saturday Mornings,

still running rings around reality with nothing but wit and timing.

Or take a quieter path, and find The Pink Panther: The Silent God of Benevolent Entropy,

who never spoke, never fought — and still managed to unbuild the world.

One tricked the system.

One refused it.

Either way, they showed us how to survive it.

Discover more from Genex Geek

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Nobody worships the old gods anymore…

LikeLiked by 1 person