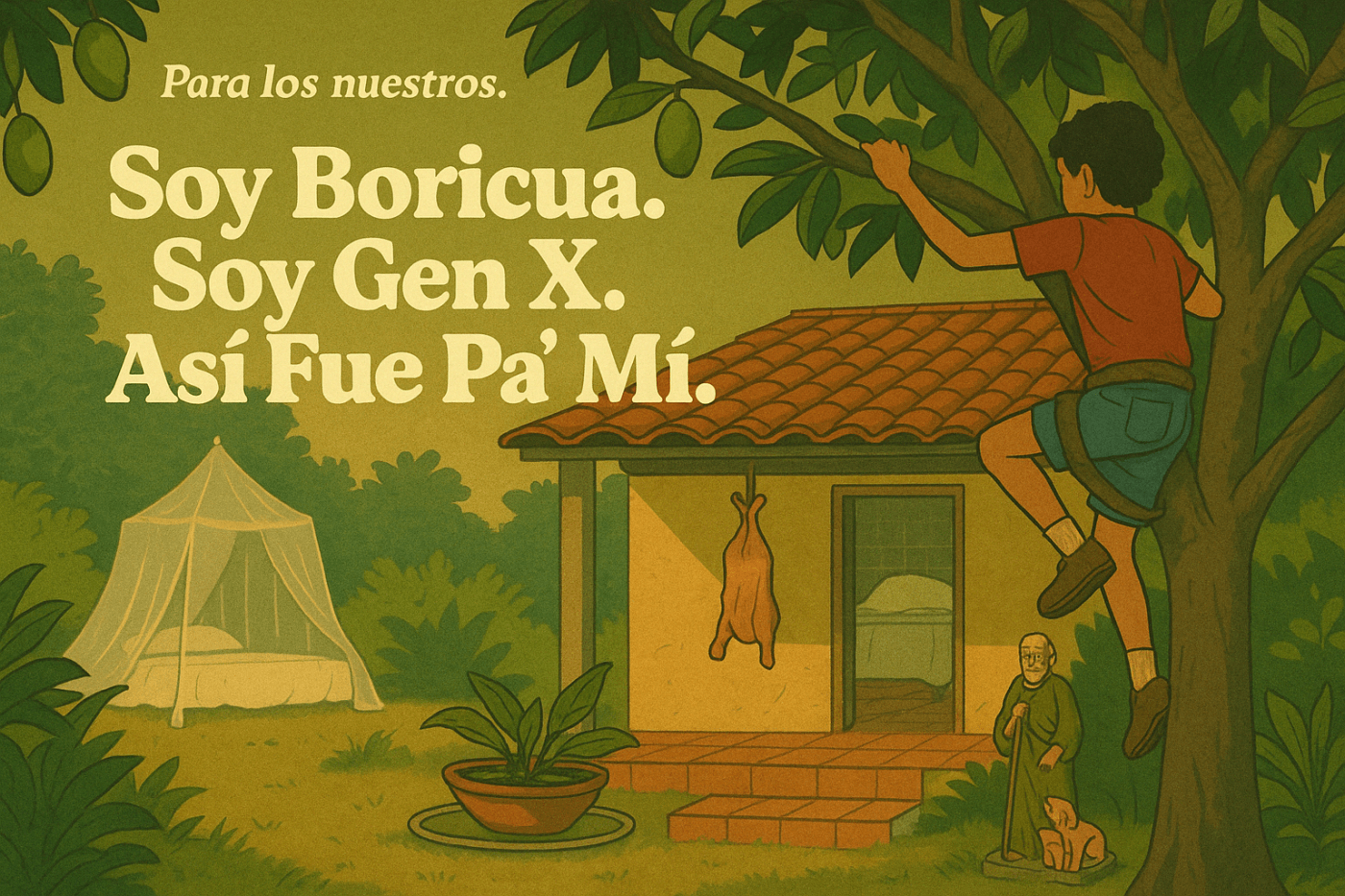

Prelude to Life in Exile in New York City

Para los nuestros.

This one’s for the Latinos from the islands.

For the Gen X kids who didn’t just grow up with Reagan and rotary phones — we grew up with saints in the living room, chickens in the backyard, and spirits in the air.

Our nostalgia smells like Mistolín and tastes like mango.

It came with mosquito nets, agua florida, and rules you didn’t question because they came from abuela — or from something older than her.

We weren’t raised the same.

But we remember just as hard.

It started in the shower, like these things usually do.

I had music playing — just some oldies mix — and Captain & Tennille came on. “Love Will Keep Us Together.”

And suddenly, I wasn’t in my bathroom. I was seven.

Memories triggered. Must have been the tune.

Back in Puerto Rico. Back in front of a TV watching Dance Fever, trying to copy the moves with a kid’s swagger.

I remember one we called “the Dead Bird.”

You’d point to the sky and say, “It was there.”

Then point to the floor and say, “Now it’s there.”

Then you’d spin.

“Dead bird!”

It was our version of John Travolta’s move from Saturday Night Fever — the one everyone knows, with the arm up, then down.

We didn’t know it was iconic. We just thought it was cool.

I danced it so much, my parents started calling me “John TresVueltas.”

It was a dad joke. A play on “John Travolta,” but with “tres vueltas” — three spins.

I didn’t get the joke back then. But I knew they were watching.

They were laughing.

And weirdly proud.

And then more memories came back.

The smell of Mistolín on tile during Saturday cleanings.

A cemetery behind the house.

Wild chickens.

Saints with puppies.

Not a story. Just a wave of what used to be normal.

Huesos y Gallinas

There was a cemetery right behind our house.

Old. Cracked. Half-forgotten.

Just a wooden fence between us and it. And for a kid, that fence might as well have been a welcome mat.

Chickens lived in that cemetery.

My mom would send me to grab eggs from near the fence.

She’d say, “Anda, ve a buscar los huevos por la cerca.”

And I’d go. Past the crooked outhouse no one used but no one went near.

Through the fence. Into the graveyard.

Grab the eggs.

Run like hell back.

Once, after one of many hurricanes, I saw bones.

Not a full skeleton. Just white pieces — clean, like the earth had exhaled too hard and loosened its grip.

I didn’t tell anyone. I just ran faster.

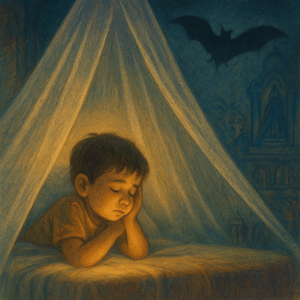

El Mosquitero

We had mosquitos. Always.

We slept under mosquito nets — mosquiteros — draped over our beds like little tents.

It made the room feel smaller. Safer. Like you were camping indoors.

Unfortunately we also had bats.

I remember waking up to flapping. Scratching. Screeching.

A bat had gotten trapped in the net.

It kept hitting the fabric, confused and squealing, trying to get out.

We screamed.

My dad came in, pulled back the net, caught it in a towel, and walked it outside.

He didn’t say much.

Just crushed it quickly.

Kindly, I guess.

It was over in seconds.

But it took a long time to sleep without fear after that.

Mangó y Coco

Sometimes we got food from the yard.

I’d climb my grandfather’s mango tree to grab the good ones before the bugs got to them.

That was the game.

Beat the flies. Pick it before it split open.

Fresh mango, still warm from the sun, eaten right there in the branches.

Other times, I’d shimmy up the coconut tree using a belt — looped around the trunk and my waist — and knock them down one by one.

No ladder. No adult supervision. Just grit and balance.

Sangre en el Sol

But some food?

Some food came with blood.

That sunroom off the house — all tile, with a drain in the middle and a hook or two on the ceiling — wasn’t for guests.

That’s where my mom hung chickens to bleed them out.

She’d grab one, snap its neck in a smooth motion, hang it, and walk away.

No hesitation. No flinching.

That was life.

That was dinner.

One year, we got dyed chicks for Easter — pink, blue, green.

I loved them. They looked like cartoon birds come to life.

The ones that survived?

They grew up.

Then they ended up on the plate too.

I also had a bunny.

I wasn’t told right away what happened to it.

But word got around.

When you were poor, conejito didn’t always make it.

And love didn’t always keep you from getting eaten.

La Monedita y La Virgen

Inside the house, we had a bowl.

Glass. Shallow. Water inside. And a plant that looked half-dead most days.

Next to it, a tiny statue of La Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre.

Every so often, my mom would drop a penny into the water.

Sometimes more than one.

The plant would shrivel when it dried, collapse like it gave up.

But as soon as you filled the bowl, it came back. Just like that.

I thought it was Santería magic.

She never explained it. She just did it.

Drop a coin. Keep the water full.

Keep the money flowing. Keep those bills paid.

El Centro

My father was a santero.

We went to something called el centro.

Not a church. Not exactly. More like someone’s living room turned sacred.

The walls were packed with saints. But they weren’t just saints.

They were masks.

Santa Bárbara — always in red, sometimes holding a sword or a chalice, with a little tower behind her.

People said she was Changó in disguise. Fire. Thunder. Power in heels.

San Lázaro had puppies licking his wounds. But really, he was Babalu-Ayé — sickness and healing in one body.

To outsiders, it looked Catholic.

But to us? It was older.

It was African.

It was alive.

They’d pour rum on the floor in the shape of a cross. Then light it.

Whoosh.

Then the drums.

Congas. Deep. Loud. Not music. Messages.

The comadres would start to dance. Some drank straight from the bottle.

They weren’t putting on a show.

They were calling.

And when one of them stopped moving — just for a second — and something else moved through her?

You knew.

Her voice would shift. Her words would twist.

She’d start pointing at people. Telling them things. Private things.

Others would fall into it too. Like dominoes.

I didn’t understand it. But I felt it.

This wasn’t brujería. That was something else — darker, whispered about.

Santería was the good kind. White magic. But everyone knew the switch could flip if someone crossed the wrong comadre.

It was all power.

Some used it for healing.

Some kept other options in their back pocket.

Even as a kid, I knew:

Don’t mess with the santera.

I picked San Lázaro as my patron saint. Or maybe he picked me?

They tied a green cloth around my wrist.

I chose him because I liked the puppies in his statue. That’s it.

I was seven.

They treated it like I’d had a vision.

Lucha No Libre

Schools had outhouses. Unused, but standing.

Kids liked to lock smaller kids in it. Cruel. That was nightmare fuel for little guys like me.

I do remember two kids trying to tie me to a flagpole.

I wanted to cry. But I remembered what my dad had told me.

“Si me entero que te dejaron llorando sin tirar ni una, te va a ir peor aquí que allá.”

If I let them hurt me without fighting back, I’d catch worse at home.

My hands were already tied to the pole.

So I waited.

And when one of them got close enough — I bit him.

Right on the lip.

He bled.

I got in trouble.

But I didn’t cry.

And that mattered.

One day in school, the teacher asked what falls from the sky.

I raised my hand and said, “The Wallendas.”

I think I had seen a story about Karl Wallenda falling off a tightrope in 1978 the night before.

I thought that was just something that happened and was educating the teacher.

Always the same record.

People laughed.

I didn’t get why.

It made sense to me.

Things fall.

People too.

I think I was supposed to say “rain”.

Limpieza Profunda

Saturdays meant deep cleaning and loud music.

My mom would play Celina y Reutilio

Songs like “A Santa Bárbara,” “A Chango,” “A Babalu-Ayé.”

It was Afro-Caribbean chant and reverb and vinyl hiss.

Where other kids had the Grease soundtrack, I had spirit music echoing through the tile while I played with my Megos.

Deep cleaning meant more than dirt, my mom didn’t just scrub floors. She cleared the house.

Spiritually.

Agua Florida was the cure for everything.

Fever? Agua Florida and a prayer.

Cold? Agua Florida and a prayer.

Breakup, fear, bad dream? Same. Splash it on your neck, whisper a few words, wait for the heat to leave your body.

If you didn’t believe in all that, there was always Vicks VapoRub. A Puerto Rican fix all.

Lagartijos y Antifreeze

I loved lizards.

I’d catch them, stick them in Tonka trucks like they were the drivers.

Then I’d crash the trucks down the ravine behind the house.

I found a glowing green puddle in the garage once. Under my dad’s tools.

Ants swarmed it like candy.

It shimmered.

Years later, I learned it was antifreeze.

Toxic. Sweet-smelling. Lethal.

Back then? I thought I’d discovered something scientific.

Sometimes I used a magnifying glass and burned them.

I was smart.

I was also an idiot.

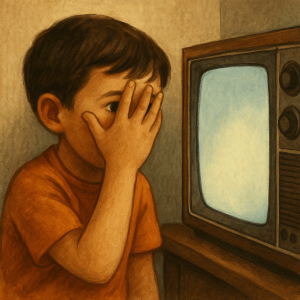

Héroes y Deseo

I didn’t just grow up on saints and cemeteries.

I grew up on “El Chavo del Ocho” and “El Chapulin Colorado”.

I watched “Starsky y Hutch” with my mom.

Watched Pedro Morales wrestle while my dad yelled at the TV like Pedro could hear him.

And then came Iris Chacón.

She didn’t sing so much as appear.

Big hair. High heels. Hips that moved like they had their own orbit.

She didn’t walk.

She arrived.

Epic.

I didn’t know what to call the feelings she stirred upon me.

But I knew they were new.

And my mom definitely changed the channel more than once.

I was seven.

Promesas y Sombras

When my sister was born sick, I saw my dad go silent.

He shaved his head. Wore white for days.

He said it was “una promesa”.

I didn’t know what he promised, or to who.

Who needed him bald?

I just knew it was serious.

Now I get it. A promise to the Orishas.

It was a deal. His habits, his appearance, his respect — in exchange for her life.

That’s how deep Santería was in our house.

Not a religion. A contract.

El Niño con el Perro

My dad believed he had a spirit walking with him.

He called him El Indio.

Not imaginary. Not optional. Just always there, granting wisdom, luck, protection, serenity..

I wondered if everyone from the centro had such exotic ones.

El Indio. El Pirata? Eleguá? La Llorona?

Was anyone walking with Steve the accountant? Bob from sales?

Probably not.

I gave myself one too. A barefoot nativeTaino boy with a hound.

He didn’t speak. He just followed me.

Watched over me.

He was my first imaginary friend.

Because my dad had El Indio.

And I wanted to be like him.

La Maleta Invisible

Then everything changed.

My parents split.

There was drama.

I wasn’t told everything.

But I know now my dad cheated.

I just remember silence. Boxes. Tension that didn’t have words.

My mom told us we were leaving the island.

“Nos vamos pa’ Nueva York.”

We weren’t taking much.

Just ourselves.

No toys. No Tonkas. No megos. No saints.

Even the spirit boy stayed behind.

I didn’t know what we were leaving.

Not yet.

That part of the story — the freezing apartment, the plastic-covered furniture, the day I met Greedo — that’s here.

But this?

This was my island.

This is what I carry.

I’m an atheist.

But I keep a little elephant my mom gave me.

Back to the door. Dollar underneath.

So I’ll never be broke.

I don’t believe in it.

But why risk it?

Thank you for reading.

From the mango trees of Puerto Rico to the video stores of the Bronx— the story doesn’t end on the island. You can follow me to New York, where Star Wars became scripture and survival meant adaptation: Greedo Was My First.

And if you want to see what it really meant to grow up in the Bronx in the 80s — loud, raw, and unforgettable — keep going: We Didn’t Just Survive the Bronx in the ’80s. We Lived It Loud..

Discover more from Genex Geek

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Comment like it’s a middle school slam book, but nicer.