Some kids are raised by parents. Others are raised by paperbacks.

I had three books that didn’t just shape me, they branded me. I didn’t know they were “important” when I found them. Nobody told me they were rites of passage. There was no curriculum or cool older kid whispering, You gotta read this. I found them the way you find all sacred things, by accident. One was sitting next to a book I already loved. One had a cover that looked like grief. One was name-dropped in a documentary about a murder.

They didn’t all age well.

One helped me understand what it means to carry pain.

One cracked my moral code and rewired how I think about good and evil.

And one turned out to be a con, and made me feel like a sucker for believing it.

This is the gospel I lived by.

And this is what happened when I looked back on the pages.

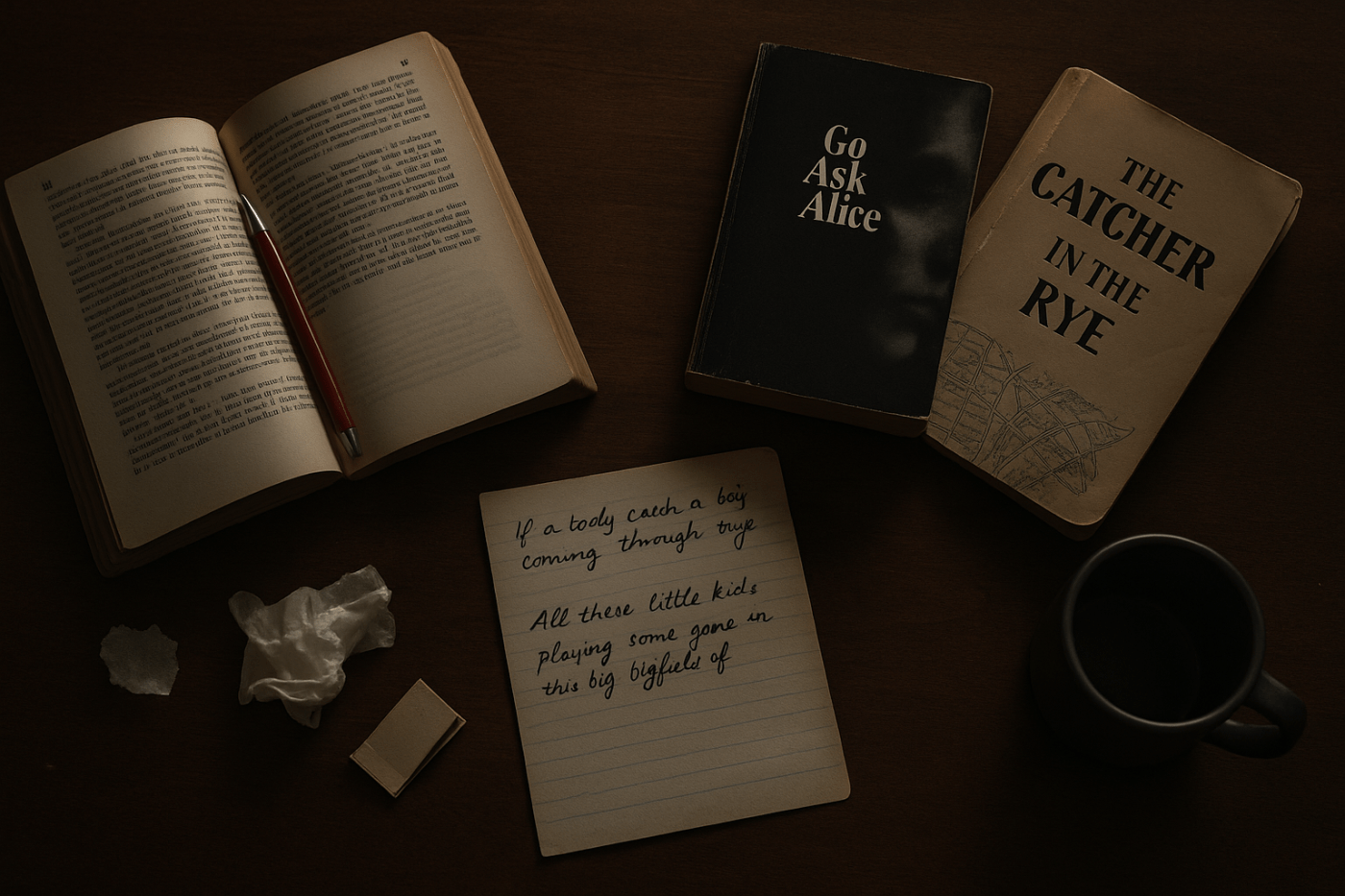

The Gospel According to Holden

From The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

If you’ve never read The Catcher in the Rye, you probably know the name Holden Caulfield. Or you’ve heard the word “phony” in that old-school, razor-tongued way. But here’s what the book actually is:

Written by J.D. Salinger and published in 1951, Catcher follows 16-year-old Holden Caulfield over the course of a few raw, spiraling days in New York City after he gets kicked out of yet another prep school. Holden’s wandering the city, avoiding home, talking to teachers, sex workers, nuns, cab drivers—anyone who might give him something real. And all the while, he’s unraveling emotionally.

His younger brother Allie died a few years earlier. His classmates are fakes. The adult world is full of sellouts. He’s holding it together with sarcasm, cigarettes, and this one idea he clings to like a life raft: that maybe, just maybe, he could be a protector.

I didn’t come to Holden Caulfield through English class or peer recommendation. I came to him through a dead Beatle.

It was the Imagine documentary. I was deep into my John Lennon phase—rebellious icon, peace preacher, angry poet. He was the kind of rock star who could spit in your face and still make you cry about it. In the film, they talked about his murder. And somewhere in there, they mentioned that his killer had been carrying around a copy of The Catcher in the Rye.

That stopped me cold.

What kind of book could live in someone’s pocket like that? Could echo through such a violent moment? I didn’t think it would justify anything—I’m not that naive. But I needed to understand it. I needed to hold that same object in my hands and see what sort of ghost it carried.

So I bought it. No idea it was famous. No clue it was a rite of passage. Just me, this strange red-covered paperback, and Holden.

And I’ll be honest: I didn’t exactly like him. He was moody. Judgmental. He sulked like it was an Olympic sport. But I couldn’t look away. Because under all the sarcasm and eye-rolling, there was this deep ache—like he’d lost something important and didn’t know how to talk about it.

And I knew that feeling.

If a body catch a body coming through the rye…

I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all.

Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me.

And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff…

All I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all.

I know it’s crazy. But that’s the only thing I’d really like to be. I know it’s crazy.

He imagines himself in a field of rye, catching kids before they fall off some unseen edge. That’s the only thing he wants to do. That’s the job he gives himself. Not hero. Not scholar. Just a human speed bump between innocence and the abyss.

When I read that, I froze. Not because it was poetic. But because it was familiar.

I was the oldest sibling in my house. My brother and sister were younger, more fragile in ways I didn’t always know how to articulate. I questioned my mother’s parenting, even as I knew she was doing her best. I felt like I had to shield them—not just from discipline or trauma, but from becoming cynical too soon. I didn’t know how to fix anything, but I wanted to be the buffer.

So Holden’s fantasy? That was my fantasy. Not to be a hero. Just to be the one who stops the fall.

It’s easy to dismiss Catcher as a book about a whiny kid who hates people. That’s how it gets written off in memes and think pieces. But that reading misses the point. Holden doesn’t hate the world. He’s trying to figure out how to live in it. He’s learning to grieve. To love. To let go. And in his own messed-up, circular way—he has an arc.

That final scene? The one where he watches his little sister Phoebe ride the carousel, and it starts to rain, and she’s reaching for the brass ring and he realizes—he has to let her?

That scene broke me.

Because that’s the real end of the catcher fantasy. He doesn’t stop the fall. He just learns how to stand back and let the people he loves take their own risks. Even if it hurts. Even if it scares him. Even if he knows what it feels like to hit the bottom.

And then there were the ducks.

“I live in New York. And I was thinking about the lagoon in Central Park… I was wondering where did the ducks go when it was frozen?”

He asks that question more than once in the book. And I couldn’t explain why it haunted me. But it did.

Because it wasn’t really about ducks. It was about displacement. About being fragile in a world that gets cold. About not knowing where to go when your environment—your family, your school, your sense of safety—stops making sense.

That question wasn’t about nature. It was about survival.

Holden isn’t stupid. He knows he can’t actually catch the kids. That the rye field isn’t real. He says it twice: I know it’s crazy. But it’s the one idea that gives shape to all the chaos. The one thing he can hold on to while everything else slips.

He’s not trying to grow up and fix the system. He’s just trying to delay the damage.

Now, as an adult, I don’t identify with Holden anymore. Not in the way I used to. If I met him today, I think he’d probably call me a phony. And maybe he’d be right.

But back then? He mattered. Not because he had wisdom. Because he had the guts to call out the bullshit. To say what most of us were too polite or too scared to say: that the world felt fake. That school was a performance. That adults were often just kids in suits pretending they had answers.

Holden’s “catcher in the rye” fantasy wasn’t a plot point. It was a moral stance. He didn’t want to teach. He didn’t want to become a parent. He didn’t even want to be happy. He just wanted to intervene. He wanted to hold space between innocence and corruption, and say: not this one.

And that mattered to me. Because I was already starting to feel like I didn’t fit into the shape the world was trying to mold me into. I wasn’t looking to blow it up—I just didn’t want to fake my way through it. Holden gave that feeling a voice.

He wasn’t a role model. But he was a signal flare. And sometimes, that’s enough.

The Gospel According to Cronshaw

From Of Human Bondage by W. Somerset Maugham

I didn’t read Of Human Bondage for school. Nobody assigned it to me. Nobody warned me. I found it on a shelf, thick and heavy and serious-looking – the kind of book you read because you think it might unlock some adult code no one’s given you yet. I didn’t understand all of it. But when I hit Cronshaw’s speech, it felt like a trapdoor opened under my assumptions.

Up until then, I thought the goal was to be good. To be brave. To be decent. You know – whatever bullshit the after-school specials were selling. But Cronshaw didn’t want to be good. He didn’t even believe in good. He wanted to live. And not in some inspirational Instagram quote way. He wanted to live in the rawest, most inconvenient sense – to feel everything, and to bow to nothing except pleasure and the inevitability of consequence.

I copied the entire speech into my journal. In red ink, no less. Like scripture. Because to me, it was scripture. This was the gospel of being human without pretending to be holy. And I didn’t know until I read it just how badly I needed someone to say that out loud.

Chapter I: Damn Posterity

“I do not attach any exaggerated importance to my poetical works. Life is there to be lived rather than to be written about. My aim is to search out the manifold experience that it offers, wringing from each moment what of emotion as it presents.

I look upon my writing as a graceful accomplishment which does not absorb but rather adds pleasure to existence.

As for posterity—damn posterity.”

Cronshaw opens by burning the sacred cow of the artistic ego. He’s not here to leave a legacy. He’s here to squeeze the juice out of the moment, not to bottle it for future generations. Writing is fine – but it’s just a hobby. Life is the thing.

It was the first time I saw someone outright reject the idea of being remembered. Everyone I knew – teachers, parents, even dumb kids in yearbook club – was obsessed with leaving a mark. Cronshaw didn’t want to leave a mark. He wanted to leave the party happy.

Chapter II: The Machinery of Fate

“The illusion which man has that his will is free is so deeply rooted that I am ready to accept it. I act as though I were a free agent. But when an action is performed it is clear that all the forces of the universe, from all eternity, conspired to cause it, and nothing I could do could have prevented it. It was inevitable.”

This was the line that broke me.

Not because it was cynical – but because it sounded true. The way you look back on your worst mistakes and realize they were a thousand tiny dominoes falling in a pattern you didn’t even know you were part of. Cronshaw isn’t angry. He’s exhausted. He knows the machine is running. He just chooses to dance while the gears turn.

It gave me a weird kind of peace. If everything’s inevitable, maybe I can stop hating myself for not choosing better. Maybe I didn’t fail. Maybe I just arrived.

Chapter III: Morality is a Costume Party

“If it was good, I can claim no merit; if it was bad, I can accept no censure.”

“I speak of good and bad… I attach no meaning to those words. I speak conventionally. I refuse to make a hierarchy of human actions and ascribe worthiness to some and ill-repute to others…”

“I am the measure of all things. I am the centre of the world.”

“But there are one or two others in the world.”

Cronshaw slices morality into ribbons. Good and bad aren’t divine truths – they’re convenience labels. He doesn’t reject them because he’s edgy. He rejects them because they don’t describe anything real.

At sixteen, this blew my mind. I was surrounded by rules, commandments, codes of conduct. And here was a man saying: yeah, none of that matters unless it matters to you.

But he’s not a sociopath. That last line – “one or two others in the world” — is his humanity poking through. He knows others are the center of their world, too. It’s not about being selfish. It’s about being honest.

Chapter IV: I Only Know Power

“Each one for himself is the centre of the universe. My right over them extends only as far as my power. What I can do is the only limit of what I may do.”

“I do not acknowledge justice. I do not know justice.

I only know power.”

Society, in Cronshaw’s world, isn’t built on virtue. It’s a mafia deal. You give it taxes and obedience, and in return, it keeps the wolves off your porch. Not because it’s good – because it works.

Reading this felt like watching the scaffolding fall off every adult institution I’d been told to trust. School, law, religion, government — not one of them was rooted in morality. Just leverage.

There’s no comfort in that. But there’s clarity.

Chapter V: The Dirty Little Secret of Virtue

“You have a hierarchy of values. Pleasure is at the bottom of the ladder…”

“The wretched slaves who manufactured your morality despised a satisfaction which they had small means of enjoying.”

“I will speak of pleasure, for I see men aim at that.”

Cronshaw goes full psychoanalyst here. Every virtue – charity, sacrifice, thrift – is just a coded way of chasing pleasure without admitting it. We don’t fear sin. We fear being seen enjoying ourselves.

This hit hard. Because I had been taught that pleasure was something to apologize for. That joy was suspicious. That suffering was noble. And here was Cronshaw saying: nah, man. They just couldn’t afford it, so they called it evil.

Chapter VI: No Applause, Just Pleasure

“If he finds pleasure in giving alms he is charitable… but it is your private pleasure…”

“I applaud myself for my pleasure nor demand your admiration.”

Cronshaw doesn’t want your standing ovation. If he helps someone, it’s because he wants to. If he drinks whiskey, same deal. He refuses to let morality co-opt his motives.

It made me rethink everything I did for “the right reason.” Was it right, or just satisfying? Did I help people because I cared or because I liked the mirror afterward?

Does it matter?

Chapter VII: The Law of Creation

“It is clear that men can accept an immediate pain rather than an immediate pleasure, but only because they expect a greater pleasure in the future…”

“If it were possible for a man to prefer pain to pleasure, the human race would have long since become extinct.”

This is where Cronshaw drops the mic. We survive because we want. Because pleasure — not morality, not God, not virtue — is the engine of creation. You don’t go to war for justice. You go because it scratches an itch somewhere deep and dark.

This idea gutted me. And then it rebuilt me. Because once you accept that, you can stop performing goodness and start choosing it. Not because it’s correct but because it settles you. Like warm soup when your chest is hollow.

I still don’t know if Cronshaw was right about everything. But I do know this: after I read him, I stopped trying to be a saint. And I started trying to be a human being. Which, some days, is the harder thing to be.

The Gospel According to Lying Alice

From Go Ask Alice (Anonymous… allegedly)

Go Ask Alice was published in 1971 and claimed to be the unedited diary of a teenage girl who spiraled into drug addiction in the late ’60s. It opened with innocence—school crushes, awkward self-image—and quickly nosedived into acid trips, homelessness, prostitution, addiction, and death. The book ended with a stark editorial note: she died three weeks after the last entry. The diary is all that remains.

Except it wasn’t a diary. It wasn’t real.

The book was later revealed to be the work of Beatrice Sparks, a therapist who used the format of a teenage diary to create a piece of anti-drug propaganda. “Anonymous” was a brand, not a voice. And the whole thing? A morality tale, constructed to manipulate young readers into fear-based obedience.

I didn’t know that when I read it.

I was in seventh grade. I found it in the school library, of all places. The cover drew me in—dark, mournful, haunted. The title reminded me of the sitcom Alice and the ‘60s counterculture I was already curious about thanks to John Lennon and the Beatles. It felt mysterious. Dangerous. Honest.

And it had bad words. That was enough to make it feel rebellious.

I devoured it. I cried at parts. I felt for Alice. She made bad choices, but I believed she was a real person—a kid overwhelmed by the world, trying to claw her way back to the surface.

It wasn’t until years later—watching a random YouTube video—that I learned the truth.

Go Ask Alice was fiction. Not just fiction. A con.

The slang made sense now. The cartoonish scenarios. The breathless pacing. It wasn’t a window. It was a stage play. Designed to scare. Marketed as truth. And I had fallen for it.

“Dear Diary, today I met a guy named ROGER who gave me a PILL and now I’m a PROSTITUTE and also probably dead. I feel so empty, but the LSD makes the trees look like pizza. Help me, Diary. I am spiraling.”

— (Not an actual quote, but it might as well be)

When you’re twelve, everything feels real if the voice shakes enough. And Alice’s voice shook. She sounded fragile. Messy. Conflicted. But when you reread it with adult eyes, the cracks show: no consistent style, no interiority, just a long list of Bad Decisions and Worse Outcomes. It reads like someone’s idea of what rebellion sounds like if they’ve only seen it in pamphlets and panicked news segments.

I wasn’t angry when I found out. I felt stupid. Like I’d handed over my empathy to a ghost, and someone behind the curtain was laughing.

It didn’t make me cynical. I already was.

It just proved me right.

Because Go Ask Alice wasn’t just dishonest. It was sanctimonious. It punished curiosity. It punished autonomy. And it pretended to care. It wanted you to think it was whispering secrets. But it was really just yelling “See what happens?!” through a sock puppet.

If Holden Caulfield was a warning about how fake the world can feel, Alice was the proof that grown-ups will absolutely lie to your face to keep you in line.

And what makes it worse is that it worked—for a while. I internalized that fear. Not just fear of drugs, but fear of going off script. Fear of becoming someone with a messy story. Someone who might be talked about in the past tense.

I don’t regret reading it. I’m glad I did.

Because Go Ask Alice taught me the most important lesson of all:

Always question the messenger.

Especially when they sound like they care.

Because sometimes, the most dangerous voice isn’t the rebel or the addict.

It’s the one pretending to rescue them.

Final Blessings (and One Exorcism)

If you haven’t already, I recommend you read—or reread—two out of these three books.

Holden still deserves your time. Even if you’ve outgrown the red hunting cap, even if you roll your eyes at his mood swings. He may annoy you—but he’ll also remind you that there was a time when you felt everything, and you weren’t wrong to.

Philip? He’ll break you open. Then he’ll hand you the pieces and dare you to make peace with them. He doesn’t offer answers. Just the truth as it is—unvarnished, unmerciful, and weirdly liberating.

As for Alice?

She can go to hell for lying to us.

Not because she faked a diary. But because she used our fear, our curiosity, our empathy—as a damn scare tactic. She dressed up manipulation as mercy. And that’s worse than fiction. That’s spiritual fraud.

So read Holden. Wrestle with Philip.

And let Alice rot in the remainder bin where she belongs.

Signed, “not bitter at all.”

Discover more from Genex Geek

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Comment like it’s a middle school slam book, but nicer.